Groove is in the heart? Wait, groove is now in court!

Forgive us if this column seems to be an excursion into the wilds of music law. But I thought we had sort of agreed that in pop, a groove, when it really works, isn’t just a few rhythmic choices bashed out by a computer or those nice people in the rhythm section. It’s the magic, it’s in the air, it’s as much a mood, a feeling. And you can’t patent a feeling, right? Wrong.

A sample is another business entirely. It’s a musical quote of the most literal kind – there in the middle of a “new” song is a little excerpt of an older one made by someone else. In music business terms it’s a profit centre – whether stolen or pre-agreed someone is going to get paid. Nile Rodgers once confided in me (in a long and very gratifying conversation), how large the music world’s addiction to Chic sampling had become, and how as far as he’s concerned this is fine. Let’s be clear, the man gets paid his dues.

And this principle, that sampling is going to cost you, has been with us for ages now. Back in the late 80s, when De La Soul dropped “Three Feet High And Rising”, their beautiful sampladelic patchwork debut, their insanely wanton use of “uncleared” samples of mainly white (!) pop hits by the likes of Hall & Oates and Eurythmics led to the rules getting nailed down pretty clearly. The story goes that after all the relevant publishing company lawyers had got home, the band had absolutely no way to make money out of this, a global hit album.

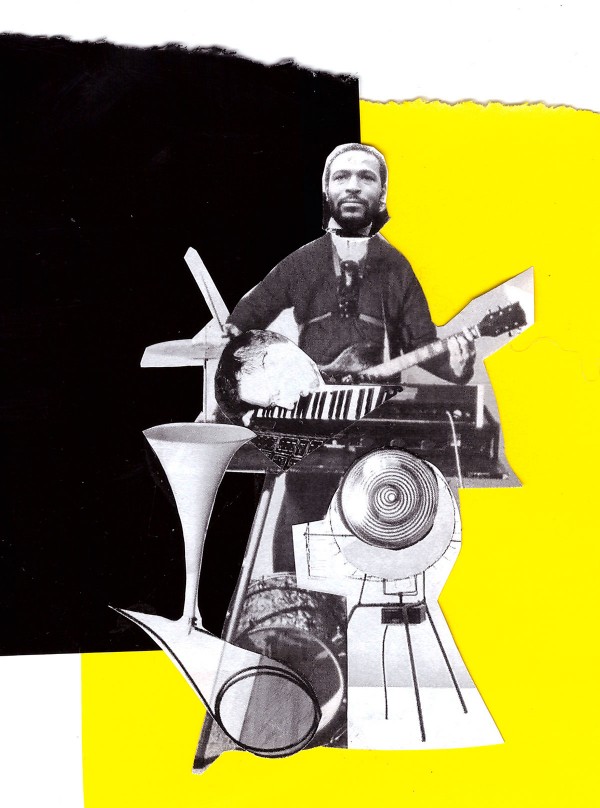

But if a sample is a well-established principle of copyright law, “ripping off a groove” most certainly is not. This is at the core of the recent Blurred Lines/Got To Give It Up court case, where the Marvin Gaye estate successfully sued Pharrell and Robin Thicke, and seems to establish that you can indeed rip off a feeling. So a new song, with a different melody and unrelated lyrics, can now be sued according to an entirely fresh set of music copyright principles. Exciting times to be a music lawyer, and terrifying ones if you make pop music for a living.

Pharrell (an artist I respect a lot, in opposite to most of my friends I think „Happy“ is the work of a decade) and Thicke were ordered to pay $7.3m damages to the Gaye estate, establishing a possibly dangerous precedent. Will Apple Records now take Tears For Fears to court because Sowing The Seeds Of Love“ borrowed the feeling of „I Am The Walrus“? Perhaps they could sue The Jam as „Start“ brings up memories of „Taxman“? Maybe Laid Back could extract some smart money from Prince as his „Erotic City“ came out after their similar-ish „White Horse“?

We used to just say pop music is always made out of other pop music, but now whether it’s citation, copy, reference, or plagiarism, pop’s creative process is becoming a legal minefield.

However, i fully support the order. Let’s be clear, “Blurred Lines” is an unashamed homage to Gaye, anyone can hear that. And it’s probably significant that a guilty conscience made Thicke/Williams take a few legal steps way ahead of the track’s release, to make sure the Gaye estate couldn’t make headway – and, well we all know how successful that was. But the point is when Pharrell wrote it, you couldn’t copyright a groove, a feeling. And now, apparently, you can.

Maybe the problem for Thicke and Pharrell was that Blurred Lines was such a divisive song, its lurid bro-sexuality and ‘hey! naked chicks!’ video felt to many like an insult to what Gaye stood for. In fact Rolling Stone magazine published a great editorial by David Ritz, lyricist of “Sexual Healing” (!), who was less bothered by the similar beats than Thicke’s dull heterosexuality, contrasting it with the exquiste multi-dimensionality of Gaye’s original:

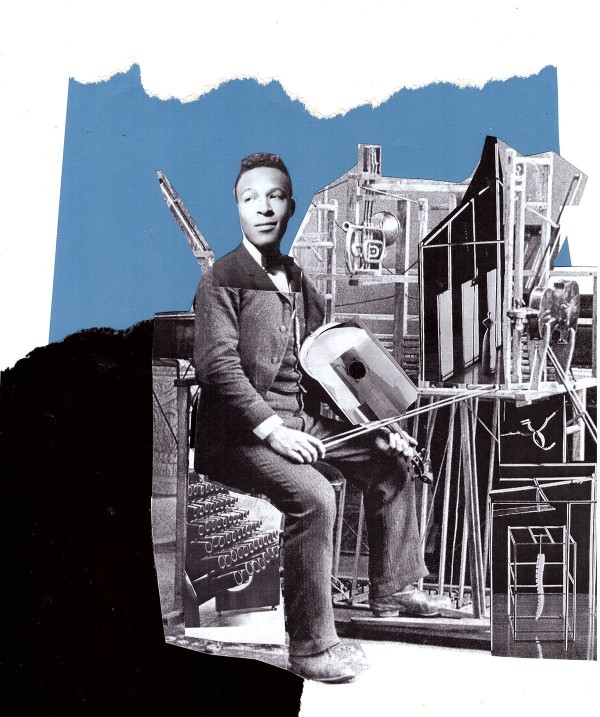

The world of cover versions, homages, and tributes to musical heros has certainly got harder to navigate in the light of this decision. On my last album, “Wonderful Frequency Band”, I’d actually created my own adaptation of “Got To Give It Up”. The contrast to “Blurred Lines” could not have been bigger: my typical sound, electronic, funky – I could never do battle with Marvin’s original irresistable groove – plus real background vocals, guitars and basses from other friend musicians, plus a highly faithful German translation of those wonderful coming-of-age-in-the-disco lyrics, which I’ve always identified with.

But sadly in this new atmosphere, the US publisher of Gaye’s work said “No” and we had to stop the album’s production mid-way, as of course they hadn’t exactly replied quickly to our request for approval. Finally, “Unaufmerksamsblindheit” found its way on to the album instead. Not too shabby itself. I guess that this stark refusal – „Please back away from any reinterpretation of „Got To Give It Up““– was caused by the early manoeuvres of the Thicke/Pharrell lawsuit. They simply wanted to avoid more terror caused by “Got To Give It Up”. (Although quite how that talented Austrian Parov Stellar made it past the publishing-police with his dance track „Keep On Dancing“, based an entire vocal sample of Marvin’s „Got To Give It Up“, I will never understand, but there you go).

My own version will now not see the light of day, hardly the end of the world, but it’s not how I planned it. Apparently copyrighted feelings get hurt rather easily.

Until next time,

Your dearest

Carte Blanchett